Mandatory, CFIUS-style screening system in place for transactions in 17 industry sectors

On 11 November 2020, the UK Government introduced the long-anticipated National Security & Investment Bill before Parliament. The new law will significantly expand the Government’s existing powers to review the national security implications of transactions and has been timed to coincide with the end of the Brexit Transition Period. The reforms follow concerns globally about foreign control of national businesses active in sensitive sectors, which have further intensified due to the COVID-19 crisis.

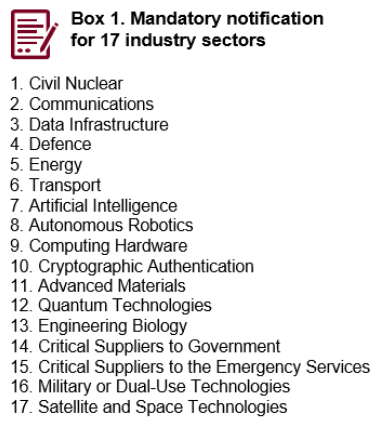

Starting in early 2021, a mandatory national security notification system will apply to acquisitions of as little as a 15% shareholding in businesses in one of 17 strategically important industry sectors (such as defence, energy, transport, communications, data infrastructure, a range of specialised technology industries as well as critical suppliers to the Government and emergency services). Outside of the 17 focus industries, notification will be voluntary.

Starting in early 2021, a mandatory national security notification system will apply to acquisitions of as little as a 15% shareholding in businesses in one of 17 strategically important industry sectors (such as defence, energy, transport, communications, data infrastructure, a range of specialised technology industries as well as critical suppliers to the Government and emergency services). Outside of the 17 focus industries, notification will be voluntary.

Businesses will need to self-assess whether they must submit a mandatory filing. The Government is publicly consulting until 6 January 2021 on how the 17 in-scope industry sectors should be defined.

The mandatory regime will be suspensory, meaning that transactions cannot complete until clearance is given by the Government. If a transaction that is subject to mandatory notification completes prior to obtaining clearance, it will be legally void.

If the acquirer fails to submit a mandatory filing, it risks significant financial penalties (up to 5% of total worldwide turnover or £10 million, whichever is higher) and criminal liability for directors.

The Government will have the ability to “call in” both mandatory transactions (that should have been notified) and transactions meeting the voluntary criteria (but where the purchaser decided not to notify). Although the Government cannot use the call-in power before the new regime has commenced, after the Bill is enacted the Government will be able to call in deals that are in progress or in contemplation as of today, 12 November 2020. Any investor engaged in a live deal affecting the UK should therefore be acting now, to consider whether the transaction raises national security issues under the new regime and whether to proactively engage with the Government in the coming weeks.

Given the stiff penalties for failure to notify under the mandatory regime and the risk of the deal being declared void after the event, businesses will likely err on the side of caution and file voluntarily where there is a possibility that their transaction may be caught by the mandatory regime or otherwise give rise to a national security issue. Overall, investors into the UK should be prepared for additional regulatory burdens, more complex risk assessments and allocation as well as delays to anticipated deal timelines.

Implications for investors

- A degree of procedural certainty for investors that submit a notification. A UK national security filing should be easily accommodated in most pre-closing timetables. The Government will be required to complete its initial screening within 30 working days, and the majority of transactions are unlikely to raise significant national security concerns requiring the deal to be called in for a longer in-depth review (consisting of an initial review period of 30 working days, that can be further extended by the Government by an additional 45 working days and for any period beyond that with the parties’ consent).

- However, the new law leaves a wide margin of discretion for deciding which transactions qualify for notification. The definitions of the 17 sectors subject to a mandatory notification (which will be finalised in separate regulations following the public consultation) are broadly drafted, leaving significant uncertainty for potential investors in the large number of UK businesses active in these areas, who may be surprised to find contemplated transactions must be notified. The lack of safe harbours or jurisdictional thresholds means the new UK regime will be over-inclusive, capturing transactions raising no plausible national security risks. Moreover, the breadth of transactions qualifying for mandatory or voluntary notification will be unprecedented, capturing acquisitions of even minority shareholdings (15%, or even lower if there is material influence) and a wide range assets (including land, tangible moveable property and anything with some commercial or economic value, such as IP, trade secrets or source codes).

- Penalties for getting the national security risk assessment wrong will be among the most severe in Europe, with the acquirer liable for fines of up to 5% of worldwide turnover, or £10 million (whichever is higher) and up to 5 years of imprisonment for directors, for failing to submit a mandatory notification.

- Failure to notify: a long “claw back” period. The Government believes that if it is not notified of a transaction that has national security risks, then it should have the ability to step in retrospectively (including after completion) to address those risks. The Government will have six months from “becoming aware” of a non-notified transaction in which to call it in for review, subject to an overall deadline of five years from the transaction. However, the five year limit will not apply to deals requiring mandatory notification – this means that there is no definitive end date by which the Government must act. The Government could, in theory, become aware of the transaction many years after closing, call it in within six months of gaining that knowledge, and impose remedies (including, as a last resort, prohibiting the deal) if it raises national security concerns.

- Deals happening now (including those outside the 17 sectors identified by the Bill) could be affected. Transactions which are in progress or contemplation in the interim period between 12 November 2020 and the start of the new regime can be called in by the Government once the Bill completes its passage through Parliament, regardless of whether they are completed before the new regime comes into effect. For transactions that do take place (i.e., complete) in the interim period, the call-in power will be retrospective and the parties will have a strategic choice as to how and whether to engage with the Government. If the parties tell the Government about a completed transaction (or where the Government has become aware of the transaction) during the interim period, the deal can be called in within six months from the commencement date of the new law. However, if parties choose not to inform the Government (risking that the Government may remain unaware of the transaction), the six months for the call-in power to be used will not start until the Government becomes aware of the deal, and the transaction could be called-in as late as five years after the commencement date.

- In practice, and especially in the early years of the new regime, businesses will likely be cautious and a large volume of voluntary notifications is expected. Although the new powers can only be used for assessing the national security implications of transactions and not to serve a wider economic or industrial policy agenda, the lines are likely to quickly become blurred. The new law does not define “national security”, leaving the question of what constitutes a national security concern to the discretion of the Government. Also, the Government’s description of the 17 sensitive sectors suggests that industrial policy concerns are driving the inclusion of some of the sectors. Given the stiff penalties for failing to notify mandatory transactions and risk of completion being nullified years after the event, many investors may not be prepared to take the risk. Indeed, the Government estimates that it will receive 1000 – 1,830 notifications a year.

In depth

Fundamental overhaul of the UK national security regime.

- Prior to the introduction of the Bill, there was no standalone foreign investment screening in the UK. Instead, the law enabled the Government to proactively intervene in transactions raising possible national security concerns.

- Although recent interim reforms made it easier for the Government to investigate six strategic sectors linked to defence and advanced technologies, overall the Government’s powers were limited and infrequently exercised. Since 2002, there had been only 12 public interest interventions on national security grounds, almost all in the defence sector.

No jurisdictional thresholds and a wide range of transactions in scope

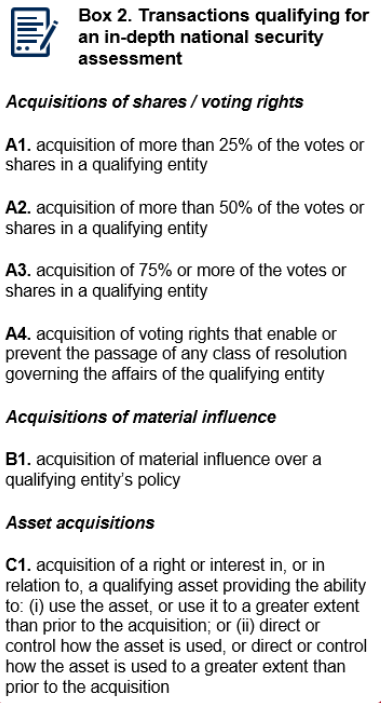

- Unlike many foreign investment systems globally, the Bill does not envisage any monetary or share of supply jurisdictional thresholds to identify qualifying transactions. Instead, the Government will have jurisdiction to call-in any transaction that constitutes a “trigger event” (see Box 2) for an in-depth national security assessment under the new regime.

- A range of legal structures (including companies, limited liability partnerships, unincorporated partnerships, associations and trusts) can be the target of a “trigger event”.

- Acquisitions of assets comprising land, tangible moveable property or any ideas, information or techniques which have industrial, commercial or economic value will also be in scope, covering purchases of bare assets including IP, trade secrets, databases, source codes, algorithms, formulae, designs/plans and software. Acquisitions of assets by consumers are excluded, other than for land or sensitive items subject to export controls.

- There will be an extraordinarily wide geographic nexus, capturing acquisitions of non-UK entities and assets (e.g., foreign IP or infrastructure) as long as they are responsible for activities in or supply of goods or services into the UK. For example, an acquisition of off-shore deep-sea cables which supplies energy to the UK could in principle satisfy the nexus requirements. Although the political focus is likely to be on foreign inward investment, the law will apply to transactions by both UK and non-UK acquirers alike.

Standalone, mandatory and suspensory national security notification system for 17 industry sectors

- A mandatory, standalone national security notification system will initially apply to certain transactions in 17 defined industry sectors (see Box 1). The Government has launched a consultation on how the 17 key sectors should be defined, to help businesses assess whether they need to notify. The list of sectors in scope, together with the final definitions, will be passed as secondary legislation, so that it can be amended from time to time in response to the changing nature of national security threats.

- A transaction in one of the 17 specified sectors will be subject to mandatory notification if it is an acquisition of shares or voting rights that constitutes a “trigger event” (see A1-A4 in Box 2). In addition, acquisitions of 15% – 24% of shares or votes will also have to be notified, but the Government will only have the jurisdiction to carry out an in-depth national security review if it determines (as part of the initial screening stage) that the acquisition amounts to the acquisition of material influence (see B1 in Box 2).

- Asset acquisitions (see C1 in Box 2) will not require mandatory notification.

- Investors caught by the mandatory regime will need to make a notification through a digital portal administered by a newly created Investment Security Unit within the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, with precise details of the process to be set out in subsequent secondary legislation. This will be a wholly separate administrative process to any merger control filing made to the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority

- Transactions falling within the mandatory regime will be prohibited from closing until the Government has completed its national security review and any completion carried through before a clearance decision would be legally void.

- Acquirers that fail to notify could face fines (the higher of up to 5% of worldwide turnover, or £10 million) and imprisonment of up to 5 years for directors.

Voluntary, non-suspensory notification system for all other transactions

- “Trigger events” that are not subject to the mandatory notification requirement (e.g., because they do not involve one of the 17 key sectors) can be notified voluntarily, if the parties consider that there are nonetheless potential national security concerns.

- Voluntarily notified transactions would normally be permitted to close pending the outcome of the national security review (unless such a step is expressly prohibited by a Government order).

Long call-in periods for transactions which are not notified

- In circumstances where the parties choose not to notify (under either the voluntary or mandatory regime), the Government may exercise its power to call-in the deal for an in-depth assessment, if it reasonably suspects transactions might give rise to a national security issue and if the transaction gives rise to one of the “trigger events” described above (see Box 2).

- The Government will have six months from becoming aware of a transaction to issue a call-in notice. This is subject to a long stop date of five years from the “trigger event” except in cases where the deal was subject to mandatory notification but where no clearance was received (in such cases the six month period will only start once the Government becomes aware of the transaction which could be many years after closing).

- Deals that are in progress or contemplation in the interim period between 12 November 2020 and the start of the new regime may be called-in, regardless of whether or not they are completed before the new regime comes into effect. The call-in power will apply retrospectively to transactions that take place between 12 November 2020 and the start of the new regime (not just those in one of the 17 key sectors identified by the Bill). For completed deals that come to the Government’s attention during that interim period, the six months will not start to run until the commencement date of the new law. If, on the other hand, the Government only gains knowledge of the deal after the new law is in place, the latest date to exercise the call-in power will be five years beginning with the commencement day.

Review process and outcomes

- Screening period: If a transaction is notified (voluntarily or as a result of a mandatory requirement) the Government will have a maximum of 30 working days from the moment the notification is declared complete to perform an initial screening. The aim of the screening stage is for the Government to decide whether to call in the deal for a more in-depth assessment.

- Assessment period: A detailed national security assessment will start once the Government issues a call-in notice. This can occur following the screening period (for notified transactions), or when the Government decides to call-in a transaction which has not been notified to it. The detailed national security assessment comprises an initial review period of 30 working days, followed by a possible extension of an additional 45 working days. Thereafter, an additional extension must be mutually agreed. The Government will have powers to require that businesses and investors provide any information that may be relevant to the transaction.

- Following the assessment period, the Government may impose any remedies it considers necessary and proportionate to prevent the identified national security risks. Remedies may include restricting the permitted share ownership levels, restricting access to commercial information or sensitive sites and (as a last resort) prohibition or unwinding of transactions.

- The call-in and assessment process will be largely non-transparent. The Government intends to only publish call-in decisions and decisions in cases cleared without remedies where this is necessary and appropriate (e.g., where one of the parties is a listed company with disclosure obligations). Only information about decisions on cases resulting in remedies will be published.

- There will be no opportunity to appeal the Government’s substantive decision on the merits (though full appeals of any civil penalty decisions will be allowed). It will only be possible to seek judicial review of decisions on grounds such as irrationality, illegality or procedural impropriety. The Government considers that it is best placed to assess the national security risk which decisions in this proposed regime are intended to address and it would not be appropriate for courts to remake these decisions.

- The national security review timelines will run in parallel with any UK merger control process conducted by the CMA. However, the Government will have the power to override any competition remedies proposed by the CMA where following the national security assessment such remedies are contrary to the Government’s national security interests.